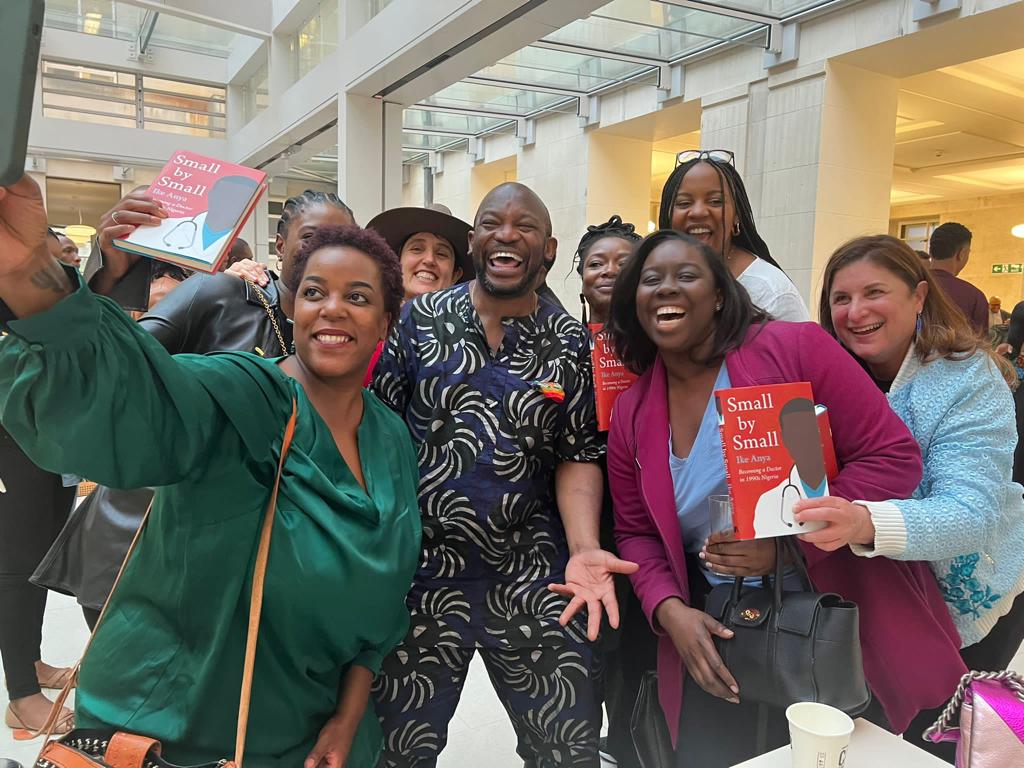

In the wake of the release of the Nigerian edition of Ike Anya’s memoir, Small by Small: Becoming a Doctor in 90s Nigeria, out now from Masobe Books, The Lagos Review presents a wide-ranging interview with the author on what triggered the book, the village behind his emergence as an author, the dysfunctional Nigerian health system and whether there will be a follow-up.

Toni Kan: Congrats again on Small by Small. What was the trigger for writing this book?

Ike Anya: As we used to say in history exams, there were remote and immediate triggers. The broader context was moving to the UK and with the benefit of distance looking at my training and early career in Nigeria. I started thinking about why I had chosen to become a doctor (had I even chosen to become a doctor?) and about the process of becoming a doctor. There were certain incidents, patients, teachers and situations which had remained very vivid in my memory and I began to relive them and to tell these anecdotes to people. I found that people were interested in them & a journalist I’d met through a friend, Jason Cowley encouraged me to write about them. I tried my hand at doing so when he became editor of Granta in the piece later published as “People Don’t Get Depressed in Nigeria”. It wasn’t published under Jason, but serendipitously years later, I met Ellah Wakatama who was deputy editor at Granta to John Freeman. They ended up publishing the piece and I had interest from agents and publishers asking if I was working on a book. As I had already been advised by Chimamanda Adichie to say yes if I was ever asked that question, I did. Given the interest, I felt it was an opportunity I couldn’t miss so I took 6 weeks unpaid leave and went off to write what became the first rough draft of Small by Small, this was in February 2013

TK: This book has been well received and it is on its way to critical acclaim, are you surprised by the reception?

IA: t’s very kind of you to say that but I’ve swung from feeling it must be absolute rubbish, given the number of rejections it had from publishers to maybe it isn’t so bad when for instance, Granta asked to publish an early excerpt and the editorial staff member wrote to say how much they enjoyed reading it. And I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the number of avid readers including fellow writers whose work I admire who have said how much they enjoyed it. But also I have found it gratifying when people like my mother said “you are such a good storyteller and my brother said he couldn’t put it down and almost took it to his friend’s birthday party after he started reading it. At the same time bookshops didn’t seem to want to stock it, media didn’t seem interested and while it appeared on a few anticipated books lists on websites and media targeting African writers, in the UK there was nothing. So in terms of expectations I’d learned to expect nothing so yes it’s been a pleasant surprise reading positive reader reviews and comments

IA: That’s an impossible question to answer, given the wide variety of what different kinds of doctors do. In a sentence I would like to say that doctors try to make life better for those who need help or care in some way, usually trying to use a mixture of scientific knowledge and skills observation, listening and communication and instruments and medicines. Not a great answer but the best I can come up with at 11pm after a long day

TK: Small by Small is a simple yet complex book in the sense that it is a simple straight forward story about your journey of becoming; a medical student and then a qualified doctor but it is also a story about life and death, laugh-out-loud funny in places and devastatingly sad and grim in others, how did you decide what to keep in and what not to include?

IA: What you describe is the reality of the process – the highs and the lows and I wanted to just pour it all out. The first draft indeed just flowed I just poured it all out on paper, but after that came the process of refinement. Slowly bits and pieces dropped through the various drafts. I was a bit stuck by the fourth draft and a piece of advice by Nancy Adimora of Afreada unlocked the final door. I’d sent her the manuscript after she had brilliantly edited my TEDxEuston story for the final souvenir programme and also my tribute to late beloved Binyavanga who introduced me to Ellah and so was responsible for this book being written. Nancy said to me – “I read it all and I loved all the details, all the stories, because I know and love you so I wanted to know more. But with each scene, with each episode, you must ask yourself, why would this matter to the average person in Tesco picking up this book? If you can’t justify it then cut it out!” And that was like scales falling from my eyes, I was able to use that and cut a lot more than I’d been able to before then

TK: It is pitched as a memoir, which makes it a personal story but it is also a profoundly public story with the story of Nigeria at a difficult period of its history managing to intrude every once in a while. How did you manage this balancing act where it does not become a jeremiad?

IA: I’ll confess I just had to check the meaning of jeremiad. I think there are two principles that guided me or perhaps influenced me – the first is that old trite saying that the personal is the political which I first came across at about the age of 16 in the context of reading about women’s rights and which I continually see examples of in so many contexts every day. So in that sense, I could not divorce my story from what was happening in Nigeria; the two were inextricably linked and so that flowed naturally. The second principle was that of balance, perhaps subconsciously influenced by the Igbo belief in the concept of duality, what Achebe articulated as ife kwulu, ife a kwu debe ya! Where something stands, something else stands beside it. So in my view, you can’t just have a lamentation of woes. Surely even in the darkest moments, there are pinpoints of light. Even during the Biafra war, there were parties, weddings and celebrations. And in some ways, perhaps, I wanted to paint a realistic picture of what it was like training as a doctor in Nigeria – some high points, often not dissimilar to training in any other part of the world. And also some low points, completely unique to our context

TK: A doctor friend once told me that for the average doctor, the first few years of practice are akin to a serial killer with grave mistakes that lead to catastrophic results, what is your view?

IA: I don’t think I would agree, but for me the wonder is really that it isn’t. The first time you are alone in the emergency room, you are petrified of sending anyone home, you want to keep them all in for observation lest you send someone with a serious ailment home and they deteriorate. And yet somehow in a mixture of science and art and experience, you begin to feel able to say “let’s keep her in for a few hours and let the surgeons come and review” or “take the baby home and give her two tea spoonful of this medicine 3x times a day and she should be fine. I think part of it is also about the structure of the training and the support or supervisory processes that, in my view and my experience, minimise the chances of catastrophic errors being made. But there is a lot that goes on via the “see one-do one-teach one” that makes you think “Hmm”, like my first experience as a house officer being called to set up an intravenous cannula having never done one before.

TK: Caring, healing and death are the hallmarks of medical practice. I know your clinical practice is far behind and you are now a public health expert operating at the intersection of policy and strategy, did you ever get used to patients dying on your watch?

IA: I don’t think any doctor or nurse ever fully gets used to losing patients under their care, no matter the circumstances. With time, we tend to put on a more blasé attitude but that’s often more a way of protecting ourselves from thinking too deeply and being too scarred by the reality. I think it always remains difficult and even with the most experienced, there will always be cases that hit home harder than others, not always for obvious reasons. At the end of the day, we are all human and you can’t help being reminded of your own mortality whenever you confront death

TK: The case of Mama and Chukwuebuka were particularly harrowing, now as a public health expert and the work you do in advocacy, what do you do to educate people about balancing faith/blind belief and medicare especially in a Third world country like Nigeria?

I find it very interesting how in a country like Nigeria, you very quickly absorb the line to take when communicating with patients around faith, healing and medication. You see doctors and nurses deploy the arguments every day and so it becomes second nature- basically to say “Look, you know, don’t you think that God gave us the knowledge and skills to devise these treatments and make them available; so using them is not going against divine will.” That seems a pragmatic way of achieving the goal of patient buy-in while respecting their beliefs.

TK: Now as a public health expert, do you miss the hospital ward and the adrenaline rush that comes with each day?

IA: There are many potential sources of adrenaline even in public health, when dealing with a fast-moving rapidly developing incident or trying to bring an outbreak under control; or even trying to make sure that immunisations get to the right people at the right place at the right time. Whenever I find myself in a hospital or clinical setting, there’s nostalgia from remembering those days but it’s not nostalgia that draws me back to the wards, I like to describe it as being like the nostalgia you might have about your school or university days. You might remember them fondly but you don’t necessarily want to go back and relive them

TK: In the Granta essay that gave birth to this book, you are in Abuja, far away from Enugu and Lagos where it all began, considering that this book ends just as your House Officer days come to its conclusion, are we to expect another in the future considering how successful this already is?

Just a point of accuracy, the Granta piece was set in Gwarzo in Kano state where I did my national service about six months after I finished as a House Officer, and not in Abuja. From Gwarzo I moved to Abuja where I worked for another three or four years before leaving for the UK. My initial plan when I started writing was to go from the day I passed my 2MB in my third year of medical school to the evening when I got a phone call offering me my first consultant job in the NHS. However I found that just getting to the end of house job year I had already written so much so I stopped there.

So yes there’s plenty more material but there are also other books I want to write – about my family history, about the things I’ve learned in my life journey, so who knows. My focus for now is to try and get Small by Small into as many peoples’ hands as possible. I don’t mind if people read it and don’t like it, but I would hate for people not even to know it exists and therefore never have the opportunity to read and decide for themselves. If that’s successful and there’s an indication that there’s an appetite for more, then….