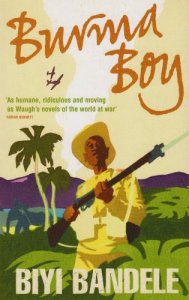

Burma Boy, Biyi Bandele, Farafina, 212pp,

Of two abiding mysteries of war, the first is that men who have seen active combat seem to always recognise each other. When war veterans who have been at bloody theatres of war write about their experiences, their pages often reek with the stench of cordite and of putrefying flesh.

The second is that war is a trade of men as distinguished from women. It is the most destructive invention of mankind yet, and the male gender, which genetically bear the Y chromosome exclusively, should know better. What we know of science today is that unlike the X chromosome, which, with close to a thousand functional genes is safe from genetic annihilation, the Y chromosome has just about eighty functional genes which are under constant danger of extermination from pollutants and environmental hazards.

Biyi Bandele came into his own as a playwright and an artist of the screen. His fiction is not as profuse as his plays but they touch on topical issues. Burma Boy, Bandele’s novel on the Burma campaign of the Second World War is remarkable first for being the first effort at giving a fictional account of that theatre of war, so many decades after, and, secondly for being an account rendered by a non-combatant.

Burma Boy bears the marks of millimetric research. No one who has read the book can contend that the author has failed to research his subject. Bandele takes us with him into the brutal if humorous world of the Chindits. He pilots us from Cairo, the city in which the man who would create the Chindits first attempts suicide to Hailakandi, Aberdeen, Tokyo, White City and his peculiar dénouement.

To find the centre of gravity of the book, two readings are required. The first to follow the story, the second to discern the mind of the author. If a reader is diligent enough to do this, two things become clear: the book is polycentric, like an automobile from a German car-plant. It really sits on four centres of gravity but the material making up the creation is so precisely weighed and distributed as to make the product feel like it has one centre of gravity. The second, flowing from the first observation is that the book is way too brief, too short for the scope of work to be done. Again, a parallel can be found in automotive engineering. It is as if, after careful calibration and deployment of a large engine, the designer put a 10-litre fuel tank in the vehicle. Bandele’s Aberdeen is not always Aberdeen as his Tokyo is not always Tokyo. In war, nothing is what it appears to be. Uncle is almost never uncle.

Burma Boy begins with an attempted suicide and ends with an attempted suicide. The first attempted suicide is sickness and drug induced. We encounter Wingate, a white officer, attempting with his hands to terminate his own life in an African city. Fate intervenes, of course, and he is rescued. He lives long enough to create the Chindits, a company of soldiers from all over the world who, under British officers, torment the Japanese in Burma using a peculiar, occidental, philosophy of the Kamikaze. The last attempted suicide in the book is by Ali Banana, overcome by grief, beside himself with human loss. He is rescued of fortune and, like Wingate, lives to fight another day.

In between these is the story of the Burma campaign, of the Chindits,

D-Section and Ali Banana. Someday it would be recognised that in recreating the ‘caustic’ exchange between British bombs and Japanese shells, evoking the courage of men under fire, painting the pity of a pitiless war of privates, Biyi Bandele deserves a medal for peace. He does it well. He is assisted, no doubt, by his own background in the North of Nigeria and his knowledge of the Hausa language. In relating the life and times of Ali Banana who became a man in Burma and not in India as his friend would have wished, Bandele tells a story of exquisite delicacy of that journey we all must make, albeit in peacetime, the journey between innocence and virtue.

For those who believe Pro patria et mori, the ‘old lie’ as Wilfred Owen put it, not even that belief can justify the effective ending of prime human lives which was the Burma campaign, which is war. To Bandele’s credit, he recreates the siege of D-Section in White City effectively. Other minutiae of war: the shootings, the shock and random deaths, the cuckoldry, the fortuitous reprieve from certain death, are achieved. Burma Boy climaxes, fittingly, in enfilade, is carried on a dramatic grace note into afterglow and ends with a cryptic offering, in Hausa.

Bandele has done what the writers of the First World War did not do. He has written a novel, not poetry. He has done what most of the writers of the Second World War have not done, he has written a mini-epic on the senselessness and intransigence of war. He has succeeded brilliantly in telling us that war is suicide by another name, that every boy deserves to live into manhood, that we will never understand other men’s wars.

In sections, Bandele’s prose is as elegant and joyful as Akin Adesokan’s prose. This is when Biyi brings in his own canvass of recognitions. Bandele should have borrowed another leaf from Adesokan however, in allowing this human story to expend itself on the reader. There is too much of the dramaturge in the clipping of the action and sequences in Burma Boy, which is a pity.

Burma Boy is a beginning. One hopes that other, younger writers would take the baton from where Bandele hangs it to tell their own sides of this story. As the author did show, almost every Nigerian has blood kin slain in Burma. They too are Burma as they were Nigerian and so ought to be remembered. In a way, it was inevitable that Bandele would write the novel the way he did. The book is a celebration of Bandele’s own life. He did not fight in Burma but his father did, and, if his father had died in that war, there certainly would not be any Biyi to write this fantastic book. Every student of Nigerian literature should get to know Ali Banana for the same reason they should get to know Okonkwo. Ali Banana, though a boy, is archetypal. A character that will endure.