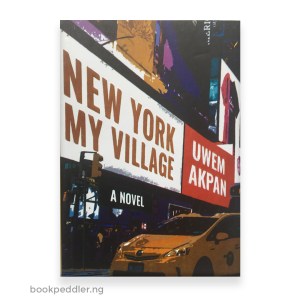

Sam Omatseye and Uwem Akpan have more than one thing in common. They are both writers and they both have written novels from a minority perspective. Their concern is the Biafran/Nigeria war, which raged and raged and raged for three years. Omatseye was the first to release My Name Is Okoro. Akpan’s New York, My Village was recently published in Nigeria and the United States. Preceding these two Biafran-themed novels are a truck-load of novels on this war whose side-effects Nigeria has not gotten out of. But unlike the efforts of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and a legion of authors of Igbo descent, Omatseye and Akpan chose to look at the issue from the sufferings of the minority.

Akpan tells his tales with brutal honesty, and shows that the sufferings of the minorities were because Biafra and Nigeria were after crude oil on their soil. He also draws attention to how the war continues to shape the lives of the children of the victims of the war. He examines their trauma, their festering wound, and many more.

Akpan tells his story as if the main character, Ekong, is narrating his ordeal to Molly, the owner of a New York-based publishing company which was about to publish an anthology of stories on the minorities. From the narrator’s tale to Molly, days after the Declaration of Biafra, the fortune of the new country was already grim. Folks who were fleeing home from Okrika had no words for what they were fleeing from. They saw local youths who refused to join the Biafran army being tossed down oil chutes to drown. Those who fled from Benin City cried about public rapes of the women leaders who rejected Biafran soldiers’ request for sex. In riverine towns like Ekoi, Ess ene, Oron, Onne, and Tungbo-Sagbama, those who refused to join the war were tagged sabos and dragged to the forest and asked to dig their graves, and later lined up, shot and buried.

E’s town known as Ikot Ituno-Ekanem was overrun by angry Biafran soldiers. A part of Our Lady of Guadalupe School was turned into barracks. Soldiers forced pupils to learn their national anthem. People were forced to fetch water for soldiers. They started killing people who did not obey them with military precision, they burnt down homes and conscripted young men, they bought over some of the elders of the town with juicy offers, and they imposed a curfew and sprayed dogs with bullets. In one instance, a father was raped in the presence of his son by Biafran soldiers and the boy kept asking why he was crying or why he was wrestling five soldiers. The boy was told they were military doctors giving him a painful type of multiple injections on his buttock. When they were done, his light blue trousers were covered in blood. The raped man was eventually accused of being a saboteur, frog-marched near Umuahia and attacked by Igbo men with sticks and crowbars for betraying Biafra.

“Papa’s discarded bloodstained blue trousers had stood in for the corpse at the requiem Mass; it was a private arrangement in the sanctity of Our Lady of Guadalupe so our Igbo parishioners would not be offended. The night Mass was celebrated by our parish priest, Father Walsh, after he had gathered my extended family to say his fellow priests in Igboland reliably told him how Papa was executed,” the narrator said.

Omatseye’s minority perspective to the Biafran story begins with blood, dust, sweat and all the violent imagery they often conjure. And there is the promise of a saucy story, whose end could be complicated. There are also hints of pain and death. With these images, he lures the reader into the world of Okoro. This Okoro is not Igbo. He is Urhobo, a proper Niger Delta ‘pikin’. The novel’s tone is protestant in nature. Instances abound in it of efforts to properly situate the feelings of the minorities of the south. At a point in the story, Okoro asks: “Why do the newspapers keep writing about Igbo pogrom when they killed everyone who was southerner except the Yorubas?”

In chapter five, a woman from the South has come to the North in search of her son. She is married to an Ukwani man and narrowly escapes being wasted because she has Yoruba tribal marks.

“Ukwanis are not Igbos,” she says.”The animals are killing everyone… Ukwanis can understand Igbo language but they can distinguish who is speaking Ukwani and who is speaking Igbo. The Igbos know who is speaking Ukwani as distinct from who is speaking Igbo.”

Then wait for this from Okoro: “But is it not worse when the language is not even close but seems to sound the same but is not Yoruba or Hausa? For instance, the Anang and Ibibio.”

Chief Subomi, who hides Okoro in his Kaduna house after he escapes Lieutenant Abdullahi’s bullets, adds: “They were not spared. They were lumped together with the Igbos in the slaughter.”

Then the ironic situation of these minorities is worsened at the point where Okoro returns home and Okungbowa is briefing him about the imminence of war.

“His father, you know, lived in Aba and there is this thing going on there called ‘leave town’. It began with criminals and never-do-wells out of the city. Now, they are asking those who are not Igbo enough to leave. It included those across the Niger. So, he heard that his father and his other relatives from Asaba had been forced to leave town.”

To Okungbowa’s statement, Okoro raises a poser: “What did they mean by not Igbo enough? In the north, everyone, including people like me were haunted and killed for being Igbo.”

We also see the Barclays Bank lady who loses her Isoko uncle in the ‘Igbo pogrom’ in Kaduna who wonders why no one was talking about that.

Both novels emphasise the futility of war. In Omatseye’s novel, Okoro’s wife says: “That (time wasting) is the meaning of this war. People died, families destroyed and cities on their knees. We have returned to where we started without all the things we started with.”

– Olukorede S. Yishau is the author of In The Name of Our Father and Vaults of Secrets